WRITER : ARCHANA K

EDITOR : SHIVRAJ PATEL

The Korean alphabet (Hangul) is the Korea’s modern writing system of the language. Language is more than a tool for communication-its carries history, culture, and national identity and pride. Korea was under Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945), the Japanese colonial government aimed to assimilate Koreans into Japanese culture, which included suppressing the Korean Language. When its native writing system, Hangul, faced systematic suppression.

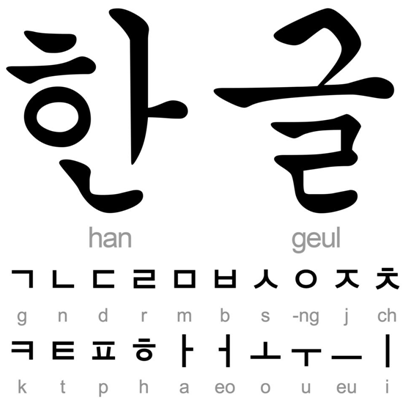

Picture Credit: WIKIPEDIA

The Korean alphabet was originally named in Hunminjeongeum (훈민정음) by the great King Sejong in 1443. The name hangul was introduced by Korean linguist Ju-Si-gyeong in 1912. The Korean word han (한) meaning great, and geul (굴) meaning script. The word han used to point out to Korea in general, also Korean script.

During the Japanese colonial period, the colonial government implemented policies aimed at assimilating Koreans into Japanese culture. The Korean language became target and replacing Korean with Japanese in education, documents and administration.

Language ban in School: Korean language education was removed from schools, by 1938, Japanese had become the medium of instruction.

Koreans Name Changes: Koreans were forced to adopt Japanese names. Having Japanese became essential for employment, legal documents, and even to food rations. Name changes symbolized the attempt to remove Korean individuality and family lineage.

Press Censorship: News papers and magazines started publishing in Korean were strictly shut down.

But Koreans did not lose their hopes families continued to speak Korean at home even when schools and public offices used Japanese language. And children still learned Korean naturally at home.

Informal community schools and religious institutions secretly taught Korean reading and writing. Christian churches, Buddhist temples, and village associations held small Hangul classes.

Korean writers and activists printed secret newspapers, pamphlets, and book in Korean language. Some publications were smuggled from abroad to circulate inside Korea, also Korean scholars and independence activists in other countries published Korean-language works. And they promoted Hangul abroad and maintained its scholarly study.

After 1921, the struggle of alive Hangul became deeply personal freedom for many Koreans. Japanese rule on Koreans had forced Korean schools and many organizations to teach most education in Japanese, and official documents were issued in Japanese. Ordinary people still kept alive to Hangul in newspapers, private schools, churches, and even in handwritten letters at home.

Organization such as the Korean-language society, (1921), really work hard to preserve Hangul despite surveillance and crackdowns, including the arrests of its members during the 1942 Korean language Society incident. Koreas Oral traditions, folk songs, stories, were maintained and passed down to younger generations, also keeping the spoken language vibrant. Because Korean survived in homes, communities, education and overseas networks, it could be reintroduced rapidly into public life after Korea’s liberation in 1945.

When Korea was independent in 1945, hangul become powerful symbol of freedom, pride and unity. Korean intellectuals and educators immediately reinstated Hangul in schools and universities, the government launched large literacy campaigns to overcome the educational gap created under colonial rule. After the Japanese colonial rule ending in the Korea, The Korean Newspapers and magazines started publishing in Korean, and there was a rebirth of literature, poetry, and historical studies. The past-liberation period also saw an earnest effort to recover lost texts, republish historical records, and teach new generations about the resilience of the Korean language under colonial rule. This process marked not merely a revival but a full restoration of Hangul to its rightful place in public life.

The survival of the Korean language under Japanese colonial rule was the result of universal informal use, teaching, and preservations by communities at home and abroad. Families, religious intuitions, underground networks, and exiled intellectuals all contributed to maintaining Hangul and Korean literacy despite official suppression. Traditions and private writings kept the language alive across generations. Because these practices continued through the colonial period, Korean remained intact as a national language and could be restored quickly to education, media, and the public life after Korea’s liberation in 1945.

Share it with your family & friends :

Jili777Slots, these slots are seriously addicting! The graphics are great and I’ve actually won a few times. Give it a shot, you might get lucky too!jili777slots

169BetLogin, a solid spot for placing your bets. The interface is user-friendly and their odds are pretty competitive. No complaints from me so far!169betlogin

Hey guys! SlotomaniaSlots is where it’s at for free slots action! So many different games to choose from, I never get bored. Plus they have cool bonuses!slotomaniaslots